Steven Young-Uhk

Director, Cooperative Research and Extension, College of Micronesia-FSM

A paper co-authored by Dr. Murukesan Krishnapillai (Research Scientist at Cooperative Research and Extension, College of Micronesia-FSM, Yap Campus) released today by the journal Nature Food presents a new global food system approach to climate change research that brings together agricultural production, supply chains, and consumption. When these activities are considered together, they represent 21 to 37 percent of total human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, the paper notes. It says that this new approach also enables a fuller assessment of the vulnerability of the global food system to increasing droughts, intensifying heatwaves, heavier downpours, and exacerbated coastal flooding. Food system responses thus play a major role in both adapting to and mitigating climate change, the authors assert.

The authors of the paper worked together on the Food Security chapter of the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special Report on Climate Change and Land. They represent a wide range of food systems from around the world, from major commodity and livestock producers to smallholder farming systems.

“The global food system approach represents a significant advance in helping producers and consumers plan effective and well-integrated climate change responses,” said Cynthia Rosenzweig, the lead author and head of the Climate Impacts Group at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies.

Concurrent with the paper, FAO is releasing today new emission statistics for the period 1990-2017 that provide the shares of agriculture and related land use in total emissions from all economic sectors, for all countries (http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/EM).

“To address sustainable development and climate challenges, the food system approach helps countries implement a range of context-specific responses on adaptation and mitigation,” said Cheikh Mbow, one of the co-authors and director of Future Africa.

“The food system is under pressure not only from climate change but also from non-climate stressors such as population growth and demand for animal-sourced products. These climate and non-climate stressors are impacting the four pillars of food security. Diversification of fo

od system by establishing integrated production systems, broad-based genetic resources and balanced diets incorporating plant-based foods can reduce risks from climate change,” said Dr. Muru.

To respond to climate change via their food systems, countries can now move beyond supply-side mitigation in crop and livestock production, which has been the traditional approach, to encompass demand side strategies, mainly dietary changes.

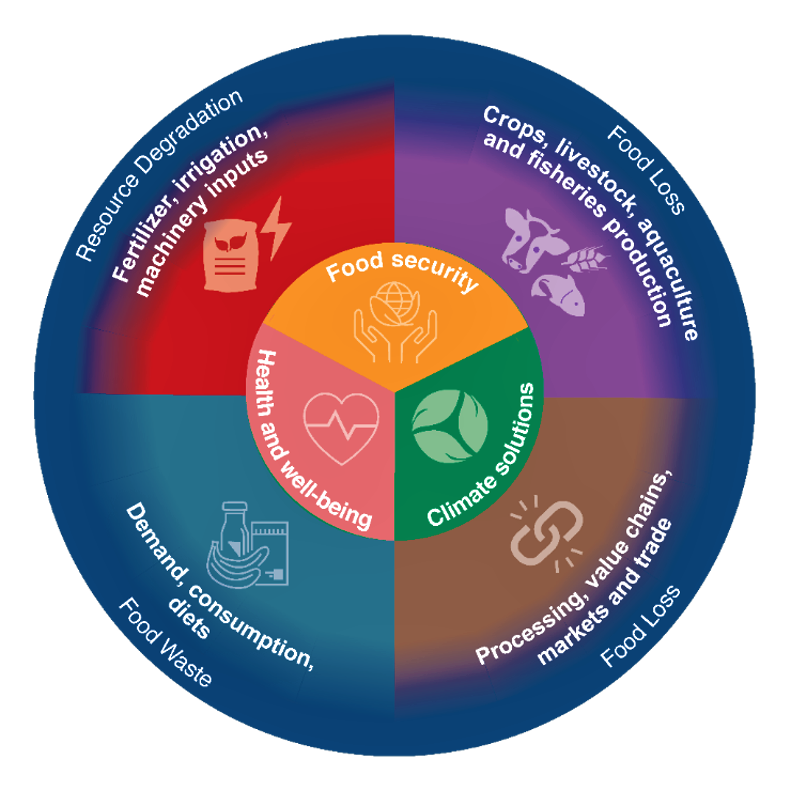

Food system components, linkages, and outcomes

One answer to the climate crisis is on our plates. Plant-based diets reduce the amount of methane emissions, a powerful greenhouse gas released by ruminants. They also require less land, thus sparing areas that can be used to plant trees and store more carbon. When both these effects are combined, the maximum amount of greenhouse gas reduction achievable through dietary change is up to 8 billion tons of CO2e per year, say the authors (total anthropogenic emissions are currently about 52 billion tons per year).

Healthy and low-emission diets that are primarily plant-based can also reduce the burden of key non-communicable diseases, such as heart disease and diabetes, say the authors.

Access the paper, here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-020-0031-z